US Arctic Region Policy 101

BLUF

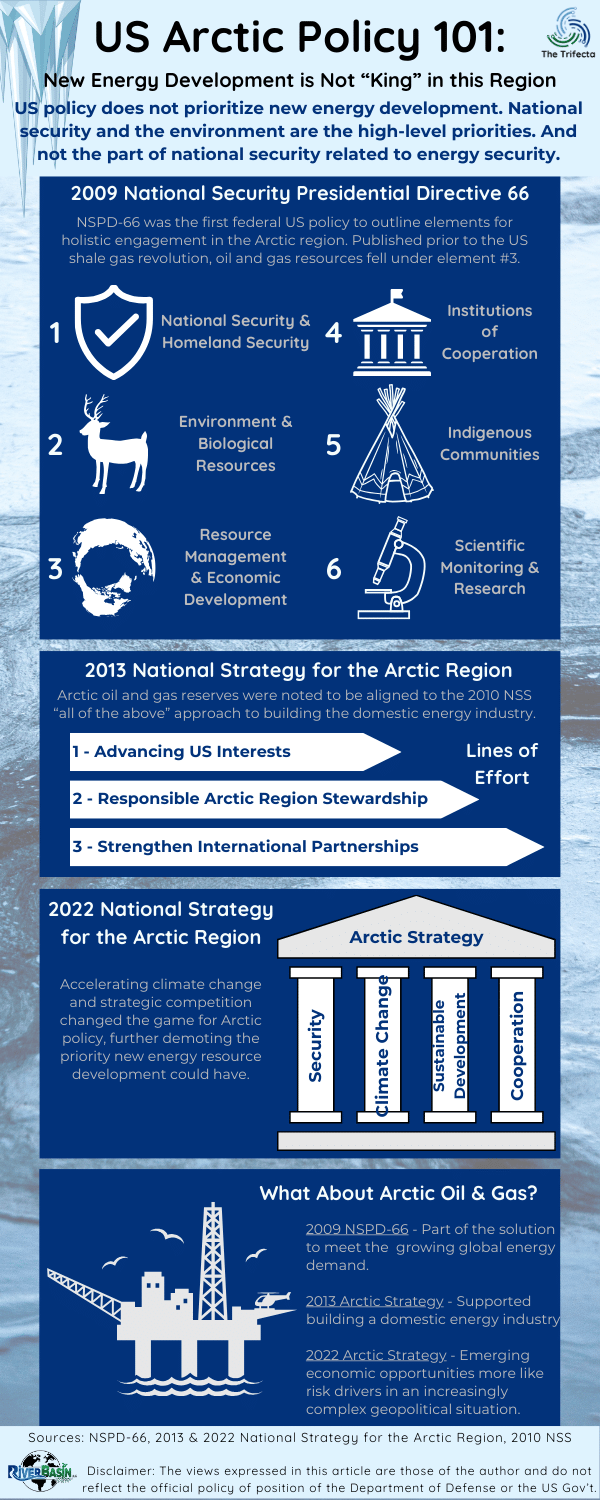

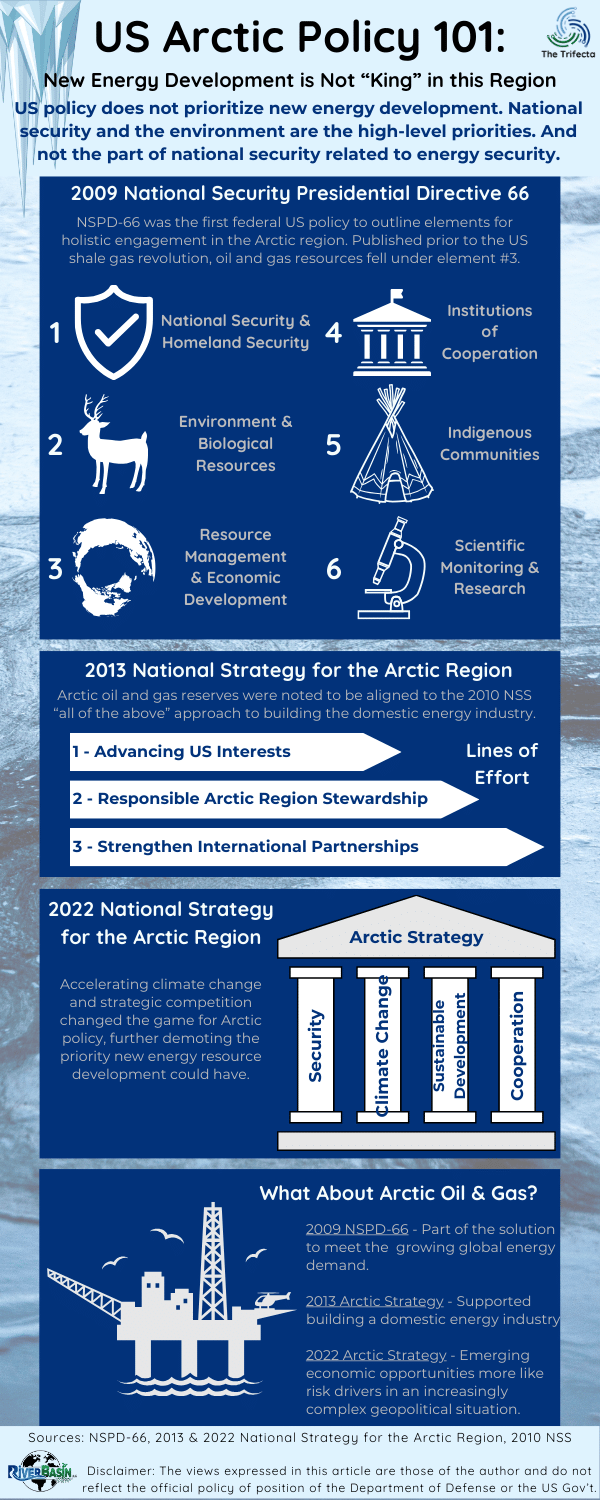

Despite decades of Arctic region oil and gas development, current US policy about the Arctic region does not prioritize new energy exploration and development. National security and the environment are the high-level priorities. Climate change is wrapped tightly into the national security concerns.

Why does this matter?

Interests of energy companies for oil and gas development are not “king” in the Arctic region. This is a contrast to the prime position energy security, and specifically oil and gas, held through the history of National Security Strategies (NSS). It is an important distinction. As covered in an earlier post (NSS 103 Energy Security), securing access to Middle East oil was viewed as a “vital interest” to US national security. Energy from the Arctic region holds no such place in the current policy.

Key Take-Aways

- Modern US Arctic region policy was established via a 2009 National Security Presidential Directive.

- In 2013, Arctic oil and gas reserves were part of the “all the above” approach to building the domestic energy industry.

- Accelerating climate change and strategic competition changed the game for Arctic policy. They turned emerging economic opportunities into potential risk drivers in an increasingly complex geopolitical situation.

Disclaimers: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. The appearance of external hyperlinks does not constitute endorsement by the United States Department of Defense (DoD) of the linked websites. The DoD does not exercise any editorial, security or other control over the information you may find at these locations.

Modern US Arctic region policy was established via a 2009 National Security Presidential Directive.

An US Geologic Survey (USGS) assessment in 2008 estimated approximately 30% of the world’s undiscovered gas and 13% of its undiscovered oil was in the Arctic region. The complete report was published in the peer-reviewed journal Science and remains the preferred estimate even in 2022.

In January 2009, the President signed an “Arctic Region Policy” with two names: the National Security Presidential Directive 66 (NSPD-66) and Homeland Security Presidential Directive 25 (HSPD-25). I will refer only to NSPD-66. As an area rapidly gaining strategic importance NSPD-66 was the first modern federal government policy describing a holistic approach to the Arctic. Six policy elements related to the Arctic Region were listed in this order (shortened for clarity here):

- National security and homeland security

- Environment and biological resources

- Natural resource management and environmentally sustainable economic development

- Institutions of cooperation

- Indigenous communities

- Scientific monitoring and research

Energy was not specifically included or named as an element by itself in Arctic region policy.

Energy would fit under element #3 about economic development. Element #3 broadly included the economic development of existing societies living in the Arctic region. For example, wild fish populations and fisheries were other significant economic issues of concern within element #3.

At the time of the NSPD-66 publication, the President viewed energy development in the Arctic region as an important part of meeting the increasing global energy demand.

About 18 months later, in May 2010, the President included a paragraph labelled “Arctic Interests” in the 2010 National Security Strategy (pg 50). Appearing at the very end before the conclusion, this four-line paragraph listed interests that mirrored those of the NSPD-66 (see above). Inclusion in the 2010 NSS reaffirmed the President’s approach to the Arctic region, including its importance for national security.

In 2013, Arctic region oil and gas reserves were part of the “all the above” approach to building the domestic energy industry.

By 2013, the US domestic gas and oil industries were booming. Building off the 2010 NSS comments about Arctic interests, the President published the first National Strategy for the Arctic Region in May 2013. Three lines of effort underpin the strategy.

- Advancing US Interests – This was anchored on freedom of navigation for sea-going vessels and aircraft, but also included energy security.

- Pursue Responsible Arctic Region Stewardship – This focused on protecting the environment and conserving resources.

- Strengthen International Cooperation – This recognized the Arctic as a shared challenge that must be addressed in partnership with others.

The 2013 Arctic strategy was published between the 2010 and 2015 National Security Strategies. Recall in the 2010 NSS, the President focused the energy section “Transform our Energy Economy” with an emphasis on developing the domestic energy industry. Oil and gas reserves believed to be in the Arctic aligned with the US “all the above” approach to building the domestic energy industry. So, it is not surprising the 2013 Arctic strategy specifically called out the Arctic region’s energy resources as a core part of the National Security Strategy. That said, responsible development and stakeholder engagement were part of the discussion about developing energy resources. Again, the policy clearly emphasized non-energy priorities even in comments concerning energy.

Two other notes for the sake of completeness:

Executive Order (EO) 13689 “Enhancing Coordination of National Efforts in the Arctic” was signed by the President in January 2015. The primary purpose of the EO was to set up the Arctic Executive Steering Committee as a mechanism to increase coordination among the many federal government activities engaged in the Arctic. The EO did not alter policy, but established another mechanism to support policy execution.

Notably, the 2015 National Security Strategy did not include a specific section on the Arctic region. It noted the unprecedented level of international cooperation needed about Arctic region issues. Potential for energy-related conflicts in the Arctic were mentioned in the energy security section of the document.

Accelerating climate change and strategic competition changed the game for Arctic region policy. They turned emerging economic opportunities into potential risk drivers in an increasingly complex geopolitical situation.

Russia spent a decade increasing its military presence in the Arctic and then (quite separately) conducted a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2021.

In October 2022, the President published two policy documents that addressed the Arctic region. One was the 2022 National Security Strategy, which included a section entitled “Maintain a Peaceful Arctic.” The section highlighted Russian investment and modernization of its Arctic military infrastructure over the last decade. Cooperation with Arctic allies and partners was the path forward to reduce risk and prevent conflict.

The other 2022 policy document was the National Strategy for the Arctic Region, which updated the earlier 2013 National Strategy. In a more robust manner than the 2022 NSS, the National Strategy outlined the changing conditions in the Arctic region. These shifts were related to climate change acceleration and the rise of strategic competition with Russia and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). As the Arctic warmed, it was becoming more accessible to potential economic opportunities. Concurrently, more non-Arctic countries were increasing their presence, investments and activities in the Arctic.

The Arctic strategy described four pillars for advancing US interests:

- Security

- Climate Change and Environmental Protection

- Sustainable Economic Development

- International Cooperation and Governance

The New Normal for the Arctic region…

This strategy was written after Russia’s 2021 full-scale invasion of Ukraine. An important distinction in the 2022 Arctic strategy is that it noted the change in circumstances for the eight Arctic nations. Since Russia invaded Ukraine, government-to-government cooperation with Russia concerning Arctic issues was “virtually impossible.” This is significant because it magnifies a fracture among the eight Arctic nations. Seven of the eight Arctic nations cooperate on Arctic matters. Only Russia doesn’t.

For energy companies who want to pursue potential energy resources in the region, the 2022 shift is notable because it demotes the priority of new energy resource development. Stated plainly, bigger issues exist – for example, avoiding conflict in the region and addressing the negative effects of climate change.

The Arctic region is not an area in which the energy transition community focuses with hopes of finding solutions. Indeed, pursuing new energy resources in the Arctic is likely now more of a risk driver to exacerbate existing geopolitical tensions.

Think About It…

- How does the Arctic region currently affect your business operations?

- Who is an expert Arctic policy in your company?

- What opportunities in the Arctic would support your energy transition goals?

- When did your company first conduct business in the Arctic region?

DOPSR 24-P-1083