Transshipment Around the Panama Canal

BLUF

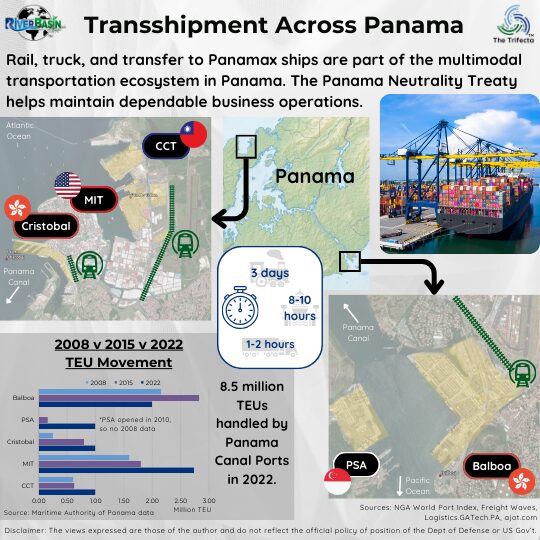

Usually, we talk about ships transiting through the Panama Canal. But a robust ecosystem of multimodal transshipment options explodes from the area around the canal, making this 50-mile (80 km) strip of land even more strategically important than many realize. The Panama Neutrality Treaty helps maintain the status quo. If it were compromised, disruptions to global commerce would be much worse than those caused by drought in Panama lately.

Why does this matter?

Transporting goods across Panama instead of sailing around South America saves roughly 22 days. While transshipment cargo volumes are small compared to those transiting the canal, transshipment is an important capability offered by Panama. Port administration of Balboa is critical because of the port’s capacity and strategic location.

Key Take-Aways

- Three primary transshipment options exist: over land bridge via 1) railcar or 2) truck and 3) transfer to a smaller ship to sail through the canal.

- Ports and terminals on both sides moved 8.5 million TEUs in 2022.

- Without the Panama Neutrality Treaty, transshipment and Panama Canal operations could be at risk.

Disclaimers: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. The appearance of external hyperlinks does not constitute endorsement by the United States Department of Defense (DoD) of the linked websites. The DoD does not exercise any editorial, security or other control over the information you may find at these locations.

Three primary transshipment options exist: over land bridge via 1) railcar or 2) truck and 3) transfer to a smaller ship to sail through the canal.

Before the larger were built, the land bridge served as a critical component of global commerce. Ships passing through the Panama Canal could only carry 4,500 20-foot-equivalent-units (TEUs). Building the larger Neopanamax locks, capable of accommodating ships with 14,000 TEUs, changed the nature of the land bridge. Rather than a core hub, the land bridge is a complementary part of a complex and growing logistics system.

Check out a previous post about energy tankers through the Panama Canal for a refresher on canal operations and ship sizes.

Despite larger locks, some vessels remain too big for the Panama Canal. Ports and terminals on either side of the Panama Canal facilitate transshipment of multiple cargo types.

One rail line runs between the two ends of the Panama Canal to facilitate transshipment.

Leveraging the over land rail route is a multistep process. Initially, a ship needs to dock at a port or terminal. Next, multiple cranes unload the ship. Transport each container to the rail yard by placing it on a truck, then transferring it to the railcar. The Panama Canal Railway provides an efficient overland route for goods to transfer to the other side of Panama, where the process happens in reverse. According to FreightWaves, it takes about three days to fully execute transshipment rail operations.

This process provides similar benefits in distance and time savings, like the Panama Canal does.

The Panama Canal Railway has the capacity to run 10 trains each way every 24 hours. Ideally, in the future, the railway will accommodate 2 million TEU each year. The Panama Canal Railway is co-owned by US and Canadian companies. It is leased to Panama for operations.

Truck and canal transshipment

The second option over the land bridge involves transferring the cargo to trucks and driving across Panama to the other port. Once trucks arrive at the other port, cargo is transferred to another ship to continue its journey via the ocean.

Last, cargo can also be transferred from a larger ship to a smaller Panamax ship for transit through the Panama Canal. For data analysis, this introduces uncertainty because some cargo may be counted twice in the data: first as TEU transshipped at a port and second as TEU transited the canal. This uncertainty also makes it difficult to put the overall cargo movement in perspective with absolute certainty.

Ports and terminals on both sides moved 8.5 million TEUs in 2022.

Transshipment is supported by two Pacific ports and three Atlantic ports. See Table 1 for a summary of the ports, their capacities and 2022 throughput.

Pacific Ports: Balboa Port has the largest capacity of the five ports covered in this post. The railroad interface is very close, making container transfer easier. Balboa’s prime geographic location supports it becoming the prime multimodal hub of the region. Balboa is owned by a Hong Kong-based company, which was explored in a previous post.

Unlike Balboa, PSA is smaller and on the opposite side of the canal entrance. Its cargo capacity is roughly half of Balboa’s capacity. Because of its position across the canal, PSA does not have direct access to the Panama Canal Railway. Instead, the port has robust trucking facilities and must truck cargo across a bridge to rail facilities by Balboa.

Table 1: Transshipment Ports on Both Sides of the Panama Canal

| Ocean Front | Owner (Country) | Capacity (TEU) | 2022 Throughput | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balboa Port | Pacific | Hutchison Ports PPC (Hong Kong) | 5 M |

2.18 M |

Hutchison Ports |

| PSA Panama | Pacific | PSA International (Singapore) | 2 M |

1.17 M |

FreightWaves |

| Cristobal Port | Atlantic | Hutchison Ports PPC (Hong Kong) | 2 M |

0.91 M |

Hutchison Ports |

| Manzanillo International Terminal (MIT) | Atlantic | SSA Marine (USA) | 3.5 M |

2.74 M |

Freight Waves |

| Colon Container Terminal (CCT) | Atlantic | Evergreen Marine (Taiwan) | 2.4 M |

1.44 M |

Freight Waves |

Atlantic Ports: The Colon Free Zone (CFZ) differentiates the Atlantic side from the Pacific side. CFZ is the most significant trading center in Latin America and the Caribbean and is surrounded by four containerized seaports, a railroad terminal and an international airport

Cristobal Port operations were rooted in California Gold Rush times and has the smallest capacity of the Pacific ports. People traveling from New York to California went through this small seaport. Though smaller, Cristobal port has a railroad interface that allows easier container movement, as well as road access to the CFZ.

On the other hand, the Manzanillo International Terminal (MIT) is the largest Pacific port and was built on a former US Naval base. MIT has developed into a massive logistics complex with warehouses, terminals, storage areas and a multimodal platform that connects to maritime, ground, rail and air transportation services.

The Colon Container Terminal (CCT) was also built on a former US Navy base. It has road access to the CFZ and the railroad.

How does port transshipment compare to container ships through the Canal?

In 2022, 1,036 container ships transited the Panamax locks, and 1,751 container ships transited the Neopanamax locks. Recall the different container numbers (TEUs) those ships can carry – 4,500 and 14,000, respectively. That means roughly 7.8 million and 24.5 million TEUs, respectively, passed through those locks during 2022. Compare this to the 8.5 million TEUs transshipped by the ports during 2022.

If we assume all TEUs are created equally (which is untrue), there were nearly 41 million TEUs moved in 2022. Of that, about 20% were moved by transshipment operations at the ports. While this is an oversimplification, it illustrates that the transshipment capacity is insufficient to contemplate accommodating 100% of annual TEUs.

Without the Panama Neutrality Treaty, transshipment and Panama Canal operations could be at risk.

From a geopolitical risk perspective, each of the five ports has pros and cons. These are primarily related to geography and ownership. For more information on the “ownership risk,” read this previous post.

Geography relates both to the location of the port, and the location of related facilities needed for operation. For example, rail interfaces are important for transshipment operations. None of the ports control the rail line, so assured access to rail is valuable.

Bridges. PSA’s location on the west side of the canal entrance makes its overland transshipment operations reliant on a bridge none of the other ports use. Compared to other ports, this is a distinct disadvantage. The Panama Canal Railway route across Panama includes other bridges, but all rail customers are reliant on those bridge and share the same risk.

Canal Entrance. Another distinction among the ports is which are located next to the canal entrance. Balboa and Cristobal Ports are next to the canal entrance. These ports are owned by the same company and recently started a 25 year concession to operate the ports. Proximity and operational authority are significant because they facilitate physical control over the canal entrance.

Table 2: High Level Geopolitical Benefits & Detractors for Transshipment Ports

| Ocean Front | Geopolitical Benefit | Geopolitical Detractor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balboa Port | Pacific | High Capacity | Rail Access | Ownership | Next to canal entrance |

| PSA Panama | Pacific | Ownership | Next to canal entrance | Bridge crossing required to access rail |

| Cristobal Port | Atlantic | Rail access | Ownership | Next to canal entrance |

| Manzanillo International Terminal (MIT) | Atlantic | High capacity | Rail access | Ownership |

Not next to canal entrance |

| Colon Container Terminal (CCT) | Atlantic | Ownership | Not next to canal entrance | No direct access to rail |

Business drives port operations currently.

The Panama Neutrality Treaty mitigates the pros and cons of the ports listed above. (Mind you, this is merely an overview, and several layers require exploration.) Economics drive business at the ports. For example, some ports are more suited for certain cargo types than others. Theoretically, economics will always drive port business. But, this is not assured. Continued adherence to the Panama Neutrality Treaty requires nations to support international law and, specifically, this Treaty. Some risks to the Panama Neutrality Treaty were covered in this post.

We have already seen how disruptions to Panama Canal operations threaten global supply chains. Drought is the primary culprit and led the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) to reduce transit slots during 2023. Reductions in operations occurred previously. The drought effects differ from the geopolitical driver discussed in this post.

What if the Panama Neutrality Treaty were compromised?

If the Panama Neutrality Treaty were compromised and Panama Canal operations (including transshipment) become unpredictable, biased, or severely limited, several logistical considerations come to mind.

- The bottleneck caused by disrupted operations would affect the global economy even more than we see with drought affects.

Transshipment operations from the ports might accommodate one-third of the annual TEUs through the canal and overland. Cargo would require aggressive prioritization or be extremely costly. We see an analogy to this with the auction slots ACP started offering and high cost some companies paid.

- Balboa Port dominates the Pacific side of the Panama Canal, which presents significant risk because of ownership.

- The Panama Canal Railway does not support a ramp-up of transshipment capacity.

- The overland truck and rails routes do not follow the same path or share bridges.

- Airports at both ends of the canal may provide alternate transportation options, but are unlikely to accommodate the scale required.

- Logistics options around the Panama Canal would quickly become overwhelmed, driving shippers to search for alternative options.

US shippers could consider shipping overland within the US and have goods arrive/depart from a west coast port like Los Angeles. Other countries can also consider this option. The sea route around South America’s southern tip is also an option.

Regardless of these options, the cost and uncertainty associated with severe and deliberate disruption to the current Panama Canal system would inflict incredible damage on the global economy and supply chains supporting it.

Think About It…

- What feedstocks or products in your business are transshipped across Panama?

- Are they transshipped via rail, truck or transfer to Panamax?

- Have your transshipped goods been affected by the drought-reduced transit slots?

- For the feedstocks or products in your business that go through Panama (canal or transshipment), what is the next best option that avoids Panama?

- How long could your business sustain operations if you had to re-route away from the Panama Canal?

DOPSR 24-P-0390