If the Top 10 Energy Companies were “countries”…

BLUF

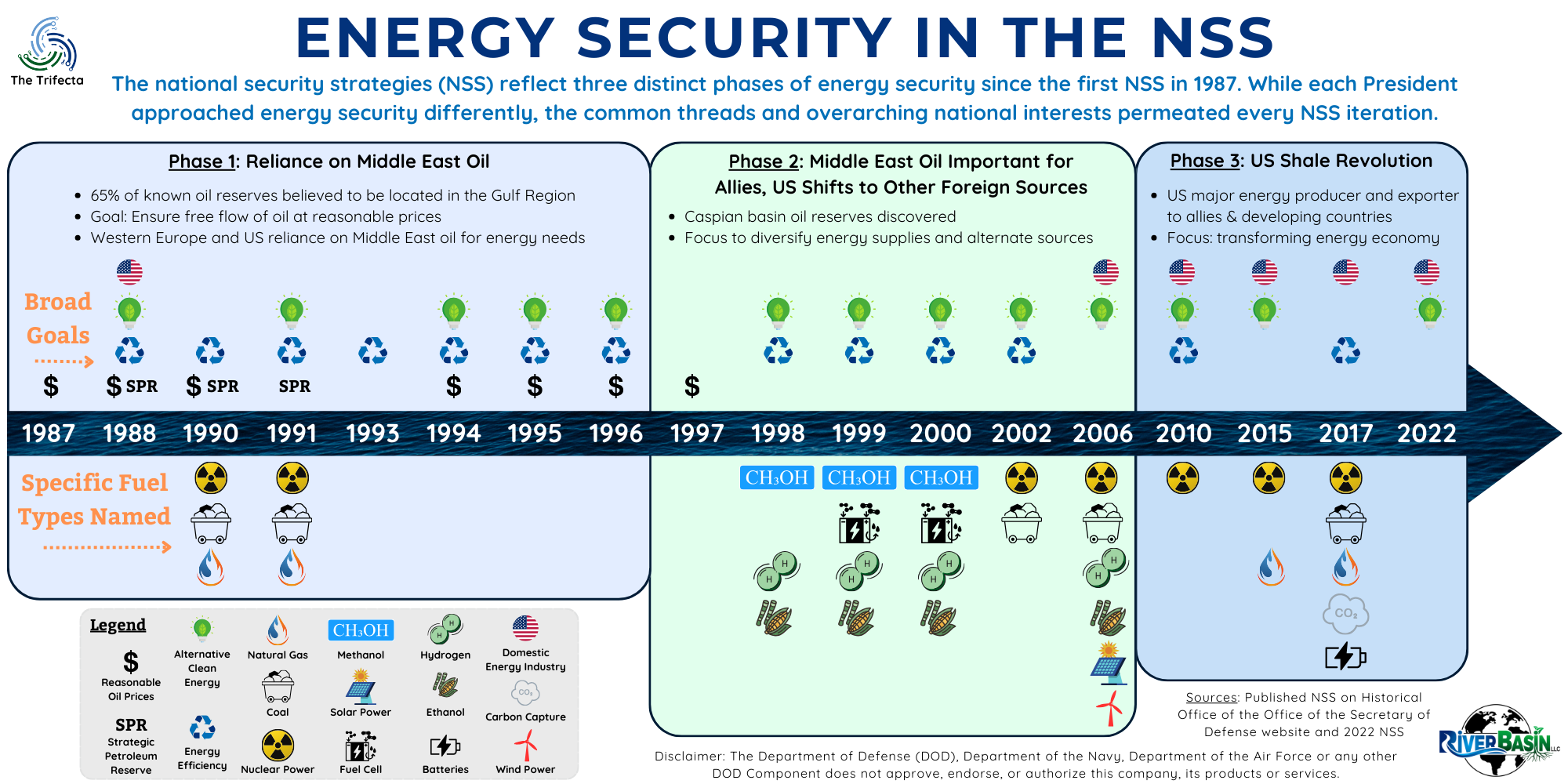

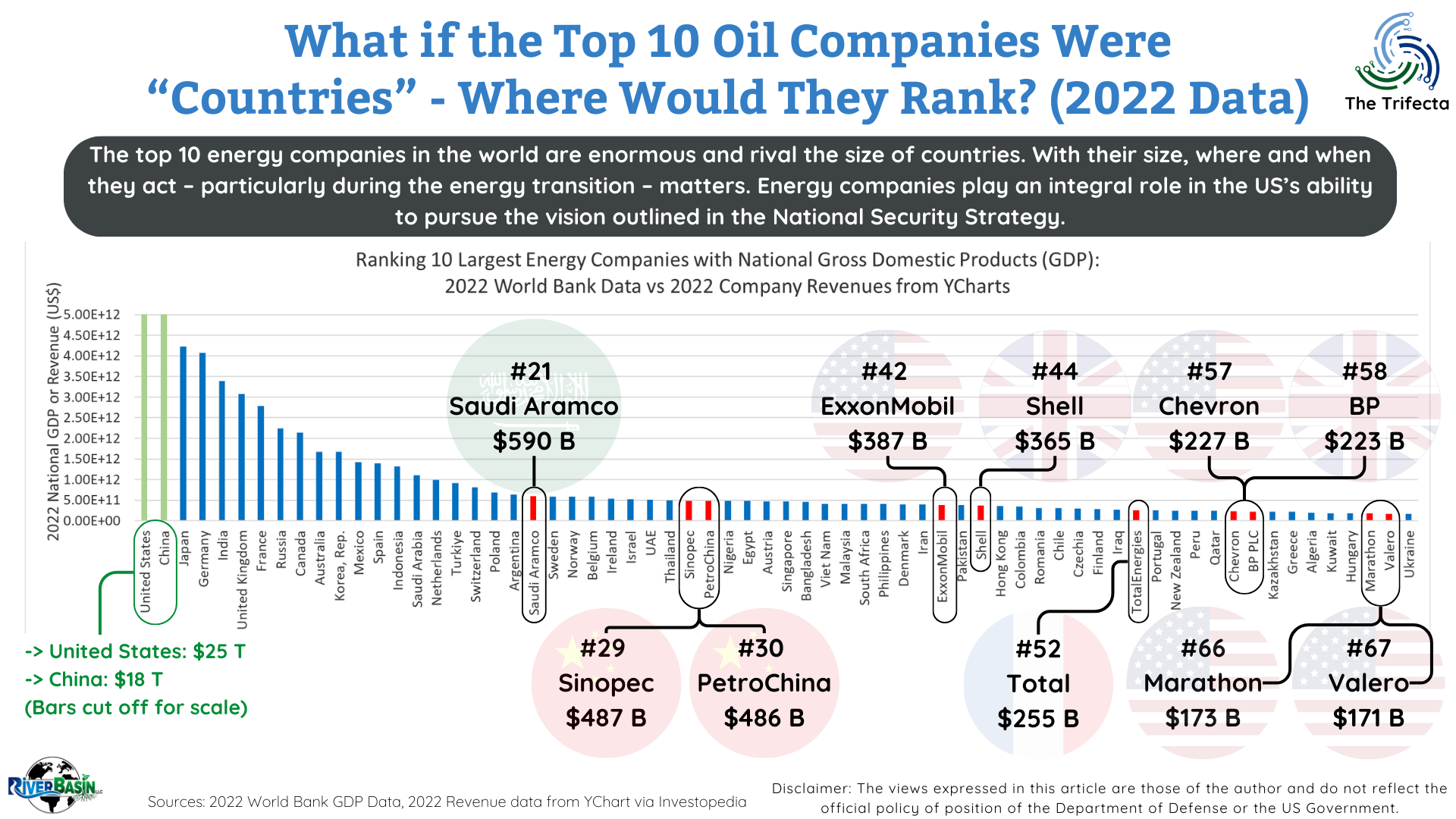

The top 10 energy companies in the world are enormous and rival the size of countries. With their size, where and when they act – particularly during the energy transition – matters. Energy companies play an important role in the US’s ability to pursue the vision outlined in the National Security Strategy (NSS), including energy security.

Why does this matter?

As we decarbonize to address climate change, operations and investments by the top 10 energy companies have the potential to serve like “parallel elements” of national power. If you missed the primer related to instruments of national power, catch up here. This post focuses on the diplomatic and economic instruments of power.

Key Take-Aways

- The top 10 energy companies are international players based on their size.

- Investments by energy companies are like another type of foreign economic assistance.

- Smaller companies matter too – Particularly during the energy transition, they may develop disproportionate influence relative to their size.

Disclaimers: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. The appearance of external hyperlinks does not constitute endorsement by the United States Department of Defense (DoD) of the linked websites. The DoD does not exercise any editorial, security or other control over the information you may find at these locations.

The top 10 energy companies are international players based on their size.

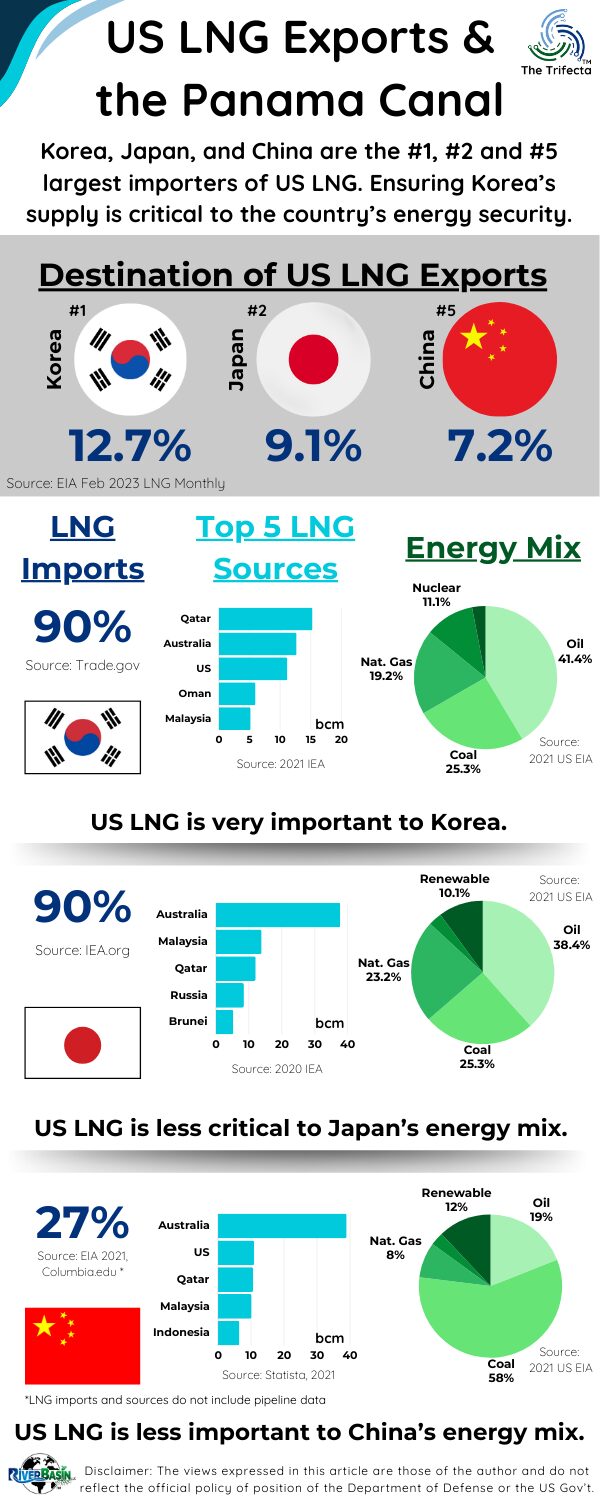

By combining data from the World Bank 2022 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Investopedia revenue from YCharts, an interesting perspective emerges (see graph above and table below).

Saudi Aramco had the highest 2022 revenue of any energy company, at $590 billion. Saudi Aramco’s 2022 revenues would make it the 21st largest country in the world relative to GDP. Argentina’s GDP (#20) was slightly higher than Saudi Aramco’s revenues, while Sweden’s GDP was lower (#22).

Sinopec and PetroChina would rank #29 and #30, respectively. These companies fell behind Thailand (#28) and ahead of Nigeria (#31) relative to GDP.

Moving to the end of the top 10 list, Valero would be the #67 largest country, ranking just ahead of Ukraine.

| Energy Company | Ranking if They Were Countries (Based on Revenue vs GDP) | 2022 Revenue ($ USD) |

|---|---|---|

| Saudi Aramco | 21 | 590 B |

| Sinopec | 29 | 487 B |

| PetroChina | 30 | 486 B |

| ExxonMobil | 42 | 387 B |

| Shell | 44 | 365 B |

| TotalEnergies | 52 | 255 B |

| Chevron | 57 | 277 B |

| BP | 58 | 223 B |

| Marathon | 66 | 173 B |

| Valero | 67 | 171 B |

Sources: World Bank and Investopedia

A nation’s diplomats and elected leaders are the traditional actors on the diplomatic stage. However, the top 10 energy companies are also significant players based on their size. For example, government officials attend the United Nations (UN) Conference of Parties (COP) events to discuss climate change commitments, and may commit their country to reduce methane emissions as part of the Global Methane Pledge. These commitments build goodwill between nations as they address shared challenges.

Separately, BP, ExxonMobil, Shell, and Total (in addition to 111 other companies) joined the UN’s Oil and Gas Methane Partnership 2.0 (OGMP 2.0) as a commitment to measure, verify and report on their methane emissions. Committing to OGMP 2.0 does not directly result in reduced methane emissions. However, commitments by enormous companies (read: might have significant methane emissions) like the top 10 bolster the credibility of the host-country’s pledge. For example, commitments by BP and Shell bolster the United Kingdom’s pledge.

Other notable risks for large energy companies

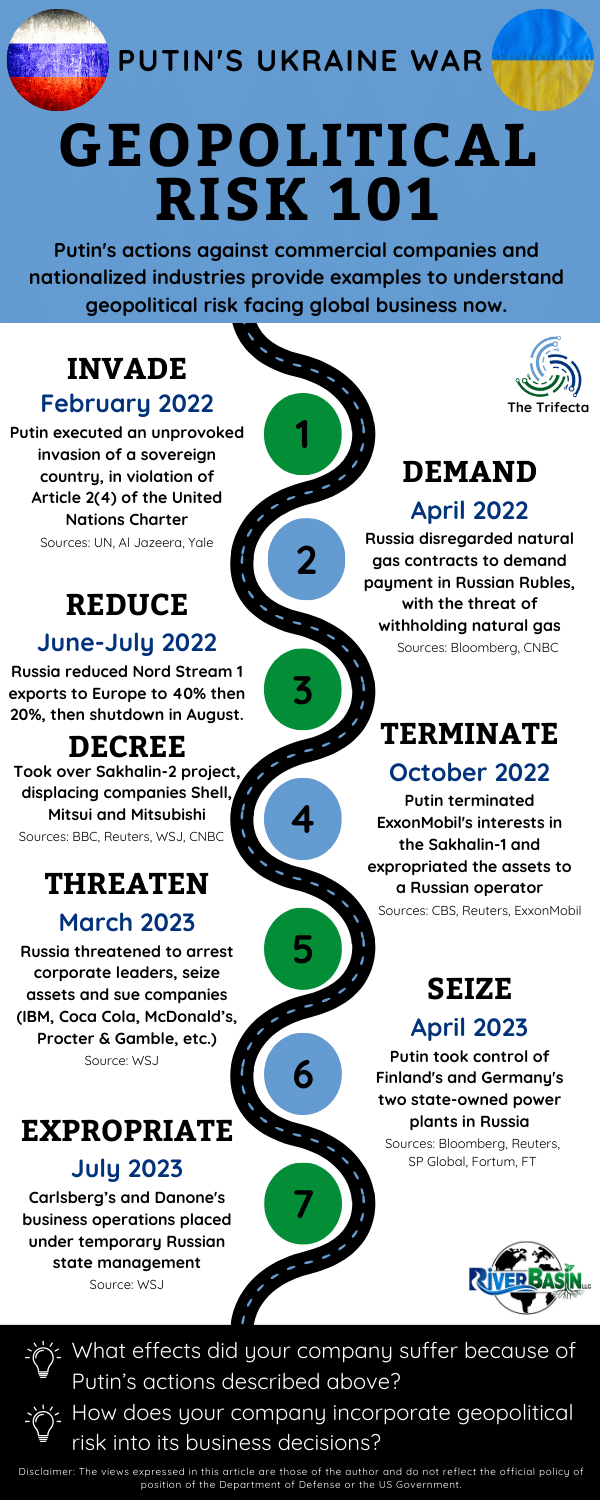

Switching gears, changes in the global geopolitical landscape increase risks to business executives traveling in foreign countries. The consequences could affect the instruments of power. For example, if business executives are barred from leaving a foreign country, they could be used as leverage in ongoing nation-level discussions. Diplomacy could play a role in resolving this. For example, if the US State Department tried to assist the departure of executives from a foreign country, they would rely on diplomatic channels to do so.

When large companies suffer major environmental accidents, it may strain the diplomatic relationship between two countries. After the BP Deepwater Horizon spill occurred, it challenged the extremely strong US-UK relationship. Navigating the aftermath consumed significant time and attention of senior government officials on both sides of the Atlantic.

Investments by energy companies are like another type of foreign economic assistance.

The economic instrument of power was a hallmark of US foreign policy for decades after World War II. After the war ended, Secretary of State George Marshall proposed the US provide economic assistance to rebuild Europe. In 1948, Congress passed the Economic Cooperation Act of 1948, which became known as the Marshall Plan. Congress appropriated over $13 billion total for European recovery during the subsequent four years. In today’s dollars using 1950 as the starting year, that $13 billion would be equivalent to $165 billion.

(For comparison, US aid to Ukraine in 2022 was $76.8 billion.)

US foreign economic assistance today within the energy sector.*

The 2022 US foreign assistance obligations within the energy sector totaled $210 million dollars (not including Department of Energy obligations). Funding from the US State Department, US Trade and Development Agency, US Agency for International Development and Millennium Challenge Corporation funded 170 activities in 63 countries or regions. Funding support projects to increase electricity availability, power generation, grid resiliency, grid connections, energy storage, utility modernization, energy markets, among others.

In contrast, ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Valero spent $13 billion, $3 billion and $788 million, respectively, internationally via capital and exploratory expenditures, according to their 2022 annual reports. While not an apples-to-apples comparison, the significance lies in the magnitude of money spent overseas developing and sustaining the energy industry. ExxonMobil, Chevron and Valero spent a combined $16.8 billion in 2022 compared to $210 million by the US government.

All the funds supported the global energy industry. Many components comprise such an integrated, complex, dynamic system. They all require maintenance or development to support continued efficacy, increase energy access throughout the world, and raise the standard of living. How the top 10 energy companies spend their money matters for all stakeholders in the global energy industry. When significant amounts are spent internationally, that funding is like a type of foreign economic assistance.

A brief note about the INFORMATION instrument of national power…

Information about company operations and investments can influence the perceptions and opinions of the population, which falls under the information instrument of power. Net-zero goals and internal spending on renewable energy (or lower carbon) are interesting to consumers and investors, who do not always share the same priorities. The perceptions—positive or negative—can create a “halo effect” that affects the country in which the companies are headquartered or operating.

ExxonMobil’s CEO, Darren Woods, captured this sentiment during his APEC CEO Summit 2023 remarks. He said “If you were to list the biggest challenges facing humankind, addressing energy poverty and climate change are at the top. And if you list the companies with a realistic chance to help improve access to energy and “bend the curve” on emissions, ExxonMobil would also be at the top.”

In those same comments, he demonstrated the compelling of information framing, as well as the magnitude of the top 10 energy companies’ ability to make a different. Darren said, “On an annualized basis, our spend [on energy transition solutions] is more than one third of the budget of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency….World-scale problems like climate change, need world-scale companies to help solve them – like ExxonMobil.”

Smaller companies matter too – Particularly during the energy transition, they may develop disproportionate influence relative to their size.

It’s not just the top 10 energy companies that matter on the international scene. As the energy transition progresses, new companies emerge and collaborate via joint ventures. These joint ventures are another way of building connective tissue between nations, populations, and economies.

One example is the relationship between Japan and Australia, which is a strategic partnership at the national level.

According to the Australia Embassy in Tokyo, “The Australia–Japan partnership is our closest and most mature in Asia, and is fundamentally important to both countries’ strategic and economic interests.” This government statement from the Embassy pertains to all national interests. Similarly, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs calls the bilateral relationship “a partnership of strength, resilience, diversity and goodwill.”

Japan and Australia enjoy a existing relationship in the energy industry. In 2022, Australia supplied 30% of Japan’s total energy needs, including two-thirds of Japan’s coal and roughly one-third of Japan’s liquified natural gas (LNG). In the renewable energy sector, activities through 2023 expanded this close partnership, even though they are business deals and not related to the government.

More Japan-Australia activity in 2023…

In March 2023, Japan-based Osaka Gas Company, acting through its wholly owned Australian subsidiary, entered an agreement with Australian-based Santos to conduct pre-front end engineering and design on a demonstration scale e-methane production project. Exporting the e-methane to Japan and other markets is the end goal of the project. Producing e-methane from green hydrogen is a focus for Osaka Gas’s net zero by 2050 ambitions.

In September 2023, Italian-based Enel Group finalized a joint venture with Japan-based INPEX by selling 50% of its renewable energy business in Australia. This deal links all three of these countries closer together. Enel and INPEX each own 50% of Enel Green Power Australia (EGPA) and will manage it together. For Enel, the deal supports its strategic plan to implement partnerships in key businesses and geographics. INPEX views the deal as a significant entry into Australia’s renewable energy market and looks for EGPA to drive the energy transition underway in Australia.

The following month, in October 2023, Japan-based Osaka Gas Company, acting through its wholly owned Australian subsidiary, signed a joint venture with Australia-based ACE Power to develop 500 MW of utility-scale solar and battery projects in Australia. Osaka Gas sees the deal as aligned to their “revived focus on renewable investments.” This renewable energy deal adds to the e-methane efforts completed several months prior in March.

Now let’s look at one example of a large energy company that is not in the top 10 – Finland-based refiner Neste.

What started in 1948 as a small refining company trying to secure Finland’s energy supply has, over the last 10-15 years, become a leading name in renewables. With a 2022 revenue of EUR 25.7 billion, EUR 9.9 billion of which was renewables, Neste’s revenue was roughly 15% of Marathon’s 2022 revenue (#66 largest “country” in the world). Yet, Neste is an industry-leader in renewable diesel, making it an attractive partnership for Marathon. The two companies closed a joint venture in September 2022 to form Martinez Renewables, which will convert one of Marathon’s California refineries to a renewable fuels plant.

Neste claimed this deal made them the world’s first and only renewable fuels maker with global capacity, based on their production footprint in North America, Asia and Europe. By retaining control of 50% of the production output in California, Neste gained a key geographic site. Marathon viewed the deal as a way to provide low-carbon intensity (CI) fuels into California Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) market. Neste is not a top 10 energy company, yet still has an impressive impact and reach, propelled by the energy transition. Where Neste operates a nd invest will affect Finland and the partner countries’ relationships on some level.

Conclusion

As energy companies pursue investments, R&D, and experiment with solutions, the future energy security of nations hangs in the balance. With an “all the above” approach to tackling climate change, the achievable mix of energy transition pathways to meet the 1.5-degree scenario remains unknown. Each nation pursues an energy security strategy. Activities by major (and minor) companies affect nations’ abilities to leverage their instruments of power to achieve their national security objectives.

*Note: Foreign assistance can be government-only or via public-private partnerships. We won’t delve into that level of detail for this post.

Think About It…

- Where is the simplest foreign country for your company to operate? Why?

- Where are your company’s international operations conducted?

- In which countries are your closest collaborators based?

- How is the impact your company has in a foreign country measured and monitored?

- When have the conditions in other countries affected your company operations or investment decisions?

DOPSR 24-P-0151