Geopolitical Risk 101: Putin Examples

BLUF

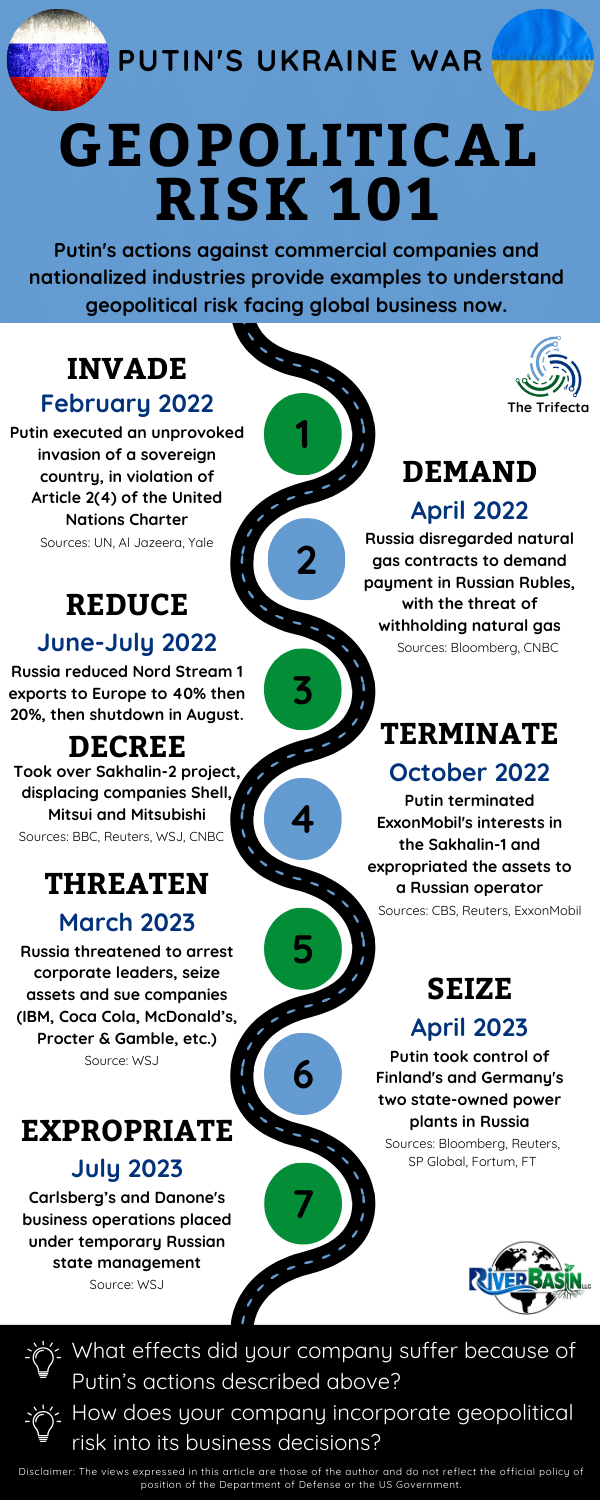

If you don’t understand what geopolitical risk means, allow Putin’s actions against commercial companies and nationalized industries to teach you. Since invading Ukraine in February 2022, Putin has done things “you just can’t do” and yet, he acted largely with impunity. Part of doing business internationally is overcoming challenging circumstances presented by other companies or host-nation governments. The difference here is Putin is the ruler of country and is meddling directly with company interests. His actions force a confluence of traditional diplomatic issues with company-specific interests, putting all affected parties in extremely challenging positions. Changes in the global geopolitical situation mean more companies may face these types of challenges in the future.

Why does this matter?

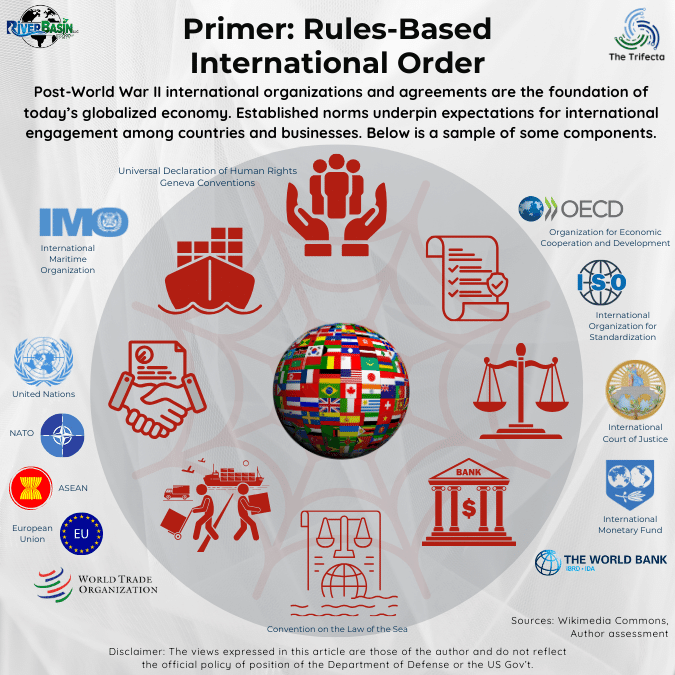

The bulk of Putin’s actions were perpetrated against the energy industry. Readers may be familiar with all the below examples. Allow The Trifecta to put them in a different context – one of Strategic Competition and geopolitical risk. At its core, Strategic Competition is a “tug-of-war” with Russia and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to maintain or change the existing rules-based international order. (This is a feature of current national security focus ICYMI.) Geopolitical risk results from this competition and threatens predictable international business norms most have spent their entire life taking for granted. To help make these concepts more tangible, this edition of The Trifecta will explore some tactical implications of doing business with an unapologetically autocratic regime.

Key Take-Aways

- Putin showed (again) his commitment to challenging the rules-based international order by invading Ukraine unprovoked.

- Putin’s actions since invading Ukraine provide energy companies with a “Geopolitical Risk 101 Course” – making his own rules and acting largely with impunity.

- As western companies depart Russian operations, their divestment options continue to decrease because Putin spontaneously orders or decrees new rules.

Disclaimers: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. The appearance of external hyperlinks does not constitute endorsement by the United States Department of Defense (DoD) of the linked websites. The DoD does not exercise any editorial, security or other control over the information you may find at these locations.

Putin showed his commitment to challenging the rules-based international order by invading Ukraine unprovoked.

Some quick recent history…

In February-March 2014, Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine. Crimea is about the size of West Virginia, compared to the Texas-like size of Ukraine. Stated differently, Crimea comprises roughly 4.5% of Ukraine’s total size. During the annexation, the smaller scale operation and covert methods employed by Putin were very different than the 2022 Ukraine invasion. (Rand Corporation published an extensive analysis capturing lessons from the 2014 events.) The nature of Crimea’s annexation is relevant because it affected the international response.

While the European Union viewed the annexation as a severe breach of European borders, the primary global response was limited to suspending Russia’s membership in the G8, implementing sanctions and the United Nations (UN) passing Resolution 68/262. Article 2(4) of the UN Charter prohibits the use of force and protects the sovereignty of nations. Resolution 68/262 reaffirmed the territorial integrity of Ukraine, as well as the importance of the UN Charter and rule of law among nations. Reaction from the international community in 2014 was underwhelming and largely contained within these standard diplomatic channels. An extensive list of nation-level responses can be found on this Wikipedia site.

Fast-forward eight years.

Putin’s 2022 Ukraine invasion was shocking because it was the first unprovoked, full-scale, multi-front military invasion of a sovereign nation in Europe since World War II. The larger scale and public, conventional military methods employed were very different than the 2014 Crimea annexation. For example, the front-line in Ukraine has been nearly 600 miles (965 km) long during the entire war, with additional fronts at times. Putin’s invasion clearly violated Article 2(4) of the UN Charter and was widely condemned by the international community for this violation of the rules-based international order.

Unlike Crimea’s annexation eight years prior, the international community responded so robustly that it is difficult to overstate. A key distinction in 2022 relevant to this post was the reaction of industry, usually under the umbrella of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Corporations ceased operations, severed business ties, made public statements, donated support, and pursued divestment of Russian assets, among other measures. The Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship compiled an extensive roundup of company responses in May 2022. This level of corporate response did not occur following the 2014 Crimea annexation.

Since February 2022, Putin continued to flaunt the rules-based international order while engaging with international businesses and other nations. The sustained and overt nature of Putin’s disregarding for international rules, particularly when dealing with corporations, should concern global businesses. Also, the victims of his actions vary in nature – some are private or public companies, while some are state-owned enterprises. The common thread for all victims is their physical location in or business connection with Russia.

Acting with impunity, Putin upended the set of rules countries and businesses expect when engaging internationally. This set of rules developed over decades and is the foundation of effective globalization. For energy companies, this should be a red flag. The global norms upon which energy companies make billion-dollar investment decisions are now at risk. Let’s take a closer look at some examples of Putin’s actions to help explain what geopolitical risk looks like.

Putin’s actions since invading Ukraine provide energy companies with a “Geopolitical Risk 101 Course” – making his own rules and acting largely with impunity.

To review, geopolitical risk refers to potential disruptions in global political and economic stability caused by factors such as conflicts, trade disputes, or policy changes between nations. These risks can affect businesses, economies, and international relations. They can cause uncertainty and potentially adverse consequences for various stakeholders.

Readers may recall many of the following events. If so, please now consider them within the larger picture of the rules-based international order and geopolitical risk. Within these events, there is a concurrent storyline about weaponizing energy. This post will not focus on that storyline to maintain focus on geopolitical risk.

After the invasion, geopolitical risk increased dramatically.

Effective April 1, 2022, Putin demanded foreign buyers of Russian natural gas must pay in rubles. Contracts with foreign companies and European countries stipulated payment to be made in Euros or US dollars. He threatened to cut off national gas supplies if buyers did not comply. In this one move, Putin unilaterally changed contract language and threatened severe consequences, with buyers having little recourse.

The saga of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline is well-known to many energy companies. (For those hazy on the geography in question, see the map in this BBC article.) Some of them likely supported efforts to mitigate the consequences in Europe. Roughly 35% of the European Union’s natural gas came from Russia via Nord Stream 1 via undersea pipeline. In June 2022, Russia reduced Nord Stream 1 exports to 40% capacity and further decreased exports to 20% of capacity in July. Putin blamed maintenance issues with the turbines in July. In August, Nord Stream 1 was shut down entirely. In September, Nord Stream 1 sustained damage ensuring it would remain inoperable. (We’ll skip the Nord Stream 2 portion of the story.)

Regardless of the reasons, the net effect for Germany and all of Europe was sudden and unpredictable change to the energy supply. Europe had no inherent ability to mitigate or ease the issue. Putin’s actions directly contravened export contracts established between entities. While we view these types of contracts as legally enforceable, the Nord Stream 1 saga showed the impotence of the victims. Drama around the Nord Stream 1 pipeline was one of the most poignant and newsworthy of Putin’s affronts to international relations during 2022.

Sakhalin-2 and Japan’s LNG Crunch

Moving on from the pipeline, Putin executed another geopolitical attack against the energy industry in July 2022. Russia decreed it would take over the Sakhalin-2 oil and gas project. Britain’s Shell and Japan’s Mitsui and Mitsubishi held a combined stake of just under 50% in Sakhalin-2. Russia’s GAZPROM held the other major stake in the project. This move was the first of Putin’s against an international petroleum project since the Ukraine invasion. Shell wrote-down their assets by $1.6 billion based on the event and Shell may have received some payment for their share of the venture several months later.

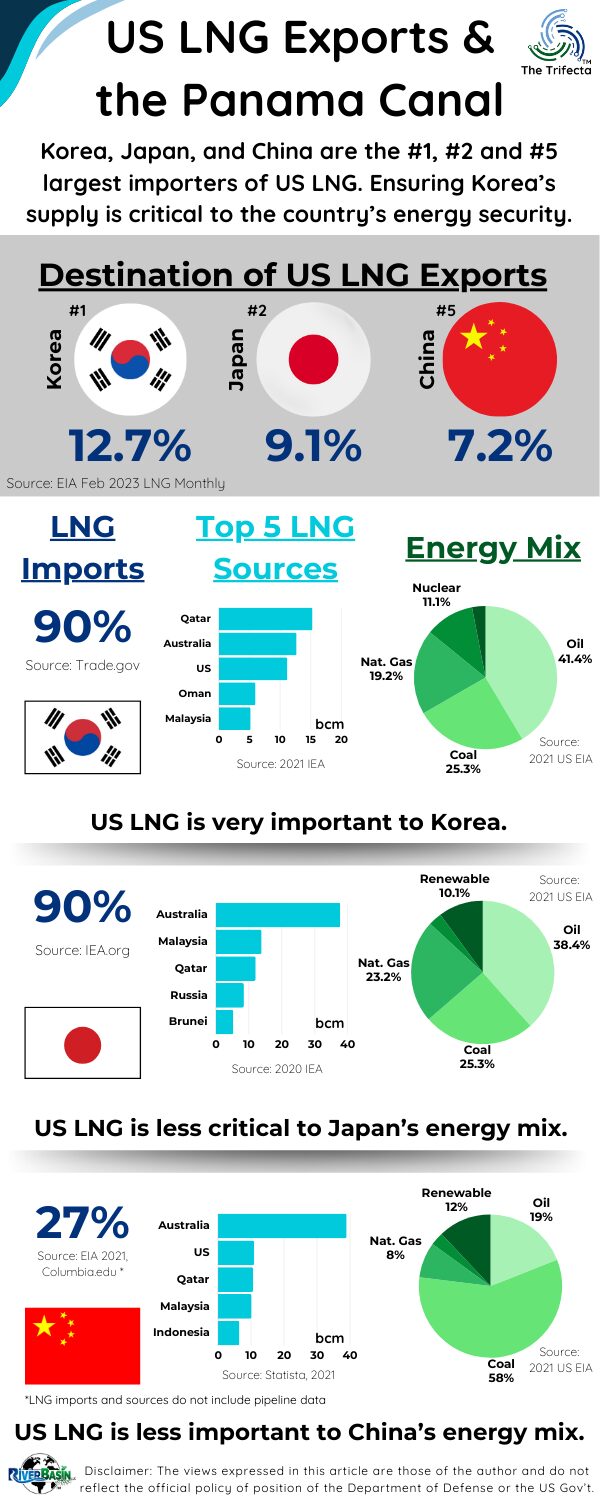

Japan is a slightly different story and shows how events in Europe can affect an average Japanese citizen removed from the crisis. Roughly one-third of Japan’s electricity is provided by LNG-burning power plants. Imports from Sakhalin-2 comprised nearly eight percent of Japan’s LNG supply. After the decree from Putin, natural gas prices in Japan increased significantly, as buyers were competing with European utilities trying to compensate for Russian-induced gas shortfalls. Many readers were likely aware of the natural gas crisis in Europe during the 2022-2023 winter because of Nord Stream 1. Fewer readers were probably familiar with similar effects in Japan for an entirely different reason. Raw materials for which companies rely on imports are at risk.

Sakhalin-1 Termination

In October 2022, Putin unilaterally terminated ExxonMobil’s interests in the Sakhalin-1 project and transferred the assets to the control of a Russian operator. Sakhalin-1 was a joint venture between America’s ExxonMobil, Russia’s Rosneft, Japan’s SODECO and India’s ONGC Videsh. ExxonMobil announced its intent to exit the Sakhalin-1 venture on March 1, 2022 and engaged with Russian stakeholders for months before Putin terminated ExxonMobil’s interests in October. The 2022 ExxonMobil annual report notes a $3 billion first quarter impairment on upstream operations as a result of Russia’s actions (p32). This again demonstrated blatant disregard for the established norms of international business behavior.

Geopolitical Risk to Western Companies

Moving on from the energy industry and into 2023, Putin expanded his scope of geopolitical attack. In March 2023, Russia’s government threatened several western companies, including Coca Cola, McDonald’s, Procter & Gamble, IBM, and Yum Brands. Threats included potential arrest of corporate leaders, seizing of assets including trademarks, and suing companies for unspecified transgressions. If acted upon, Russia’s actions would likely have business impacts on these companies, regardless of the veracity of the claims.

In July 2023, Putin signed a decree that placed local-Russian operations of Danish brewer Carlsberg (and 20% of its global work force) and French dairy company Danone under temporary management by the Russian federal state property management agency. These moves were a uniliteral and unpredictable seismic shift for both Carlsberg and Danone. Employees living in Russia were affected. Company operations had to change.

Seizing European state-owned utilities operating in Russia

In April 2023, Putin seized control of two utilities providers in Russia state-owned by European countries – Finland’s Fortum power plants and Germany’s Uniper power plants. Uniper operated five power plants with an 11 GW capacity in Russia before they were seized by Russia. Fortum operated seven thermal power plants with a 4.7 GW power generation capacity and 7.6 GW heat production capacity.

These seizures show direct action against another sovereign state and are inconsistent with the rules-based international order. Unfortunately, like the examples above, Finland and Germany had few tools available to recuperate the loss of the power plants (both infrastructure investment and operational profits) without resorting to armed conflict. Fortum formally notified Russia that it strongly objected to the decree but ended up writing down the assets to the tune of EUR 1.7 billion. Uniper reported a EUR 4.4 billion loss due to Russia’s actions.

As western companies depart Russian operations, their divestment options continue to decrease because Putin spontaneously orders or decrees new rules.

Less than a month after the invasion, businesses from around the world started closing their Russian branches or divesting their Russian assets altogether. Based on the industry and scale of Russian operations, the closure, or divestment executed by businesses would normally require many months (or years) to plan deliberately. This unexpected change likely had a costly impact on businesses. Fortum, discussed above, started working its exit strategy from Russia in spring 2022 (a year before their plants were seized) and describes their year-long process here.

Making matters more difficult, Putin’s actions in the summer of 2023 constrained business’s options for leaving Russia. In June 2023, Putin ordered legislation passed to give priority rights to the Russian government for buying any western asset for sale at a “significant discount.” He also established a requirement for Russian buyers of western assets to be fully held by Russian interests.

Uniper, for example, stated on their website they found a local buyer for their Russian business unit Unipro. However, “the political approval of the transaction is pending and uncertain” and Uniper was considering legal options in August 2023. Divesting remaining assets at a competitive price became much more difficult because of Putin’s mandates. Though counter to business norms and the rules-based international order, companies have minimal recourse and are left evaluating the least-worst options.

The events above are just the start of understanding geopolitical risk.

Energy companies would be well advised to note the varying tools Putin used against commercial and nationalized industries. The energy industry received a disproportionate slice of his ire. As the war in Ukraine continues, stay tuned for more Putin behavior modeling the geopolitical risk businesses may face in the future from unapologetically autocratic leaders.

DOPSR 24-P-0133

Think About It…

- Why do you think your business would be treated any differently from ExxonMobil, Shell, Danone, or CocaCola if you operated in an authoritarian country?

- What effects did your company suffer because of Putin’s actions described above?

- How does your company incorporate geopolitical risk into its business decisions?

- How many people at your company are working to evaluate these risks?

- Where do your critical feedstocks come from? If they are imported, from where?

- What continuity of operations plans does your company have in case events like this happen where you operate internationally?